The word “alignment” doesn’t belong to the common vocabulary of geopolitics. It is rather its negation that more than a half-century ago entered the political stage of the world. The so-called Non-Aligned Movement was founded in the midst of the Cold War at the first Conference of Heads of State or Government of Non-Aligned Countries, held in September 1961 in Belgrade the capital of what once was socialist Yugoslavia. It was initiated by Josip Broz Tito, then the president of the country, and attended by Jawaharlal Nehru of India, Sukarno of Indonesia, Gamal Abdul Nasser of Egypt and Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana. Soon over 100 countries mostly from the Third World joined the Movement, which played a significant role in the international politics in the second half of the 20th century.

Today, none of the founding fathers of the Movement is still alive. The country, where it was founded, Yugoslavia, fell apart in a civil war, without any of its successor states showing interest in the legacy of the Non-Alignment. Yet the Movement itself, although having lost any significant influence on the international politics, has curiously survived the end of the Cold War, in which it had found once its raison d’etre. This, however, seems now to be changing too.

Since recently Narendra Modi took office as India's prime minister, the world’s second-most-populous nation and one of the founding members of the Movement has openly abandoned non-alignment as the guiding principle of its foreign policy. The change is even more significant if we remember that it was in fact an Indian, V. K. Krishna Menon, who in 1953 coined the term "non-alignment" and that another Indian, Jawaharlal Nehru, first defined it as a geopolitical concept grounding it in five principles: Mutual respect for each other's territorial integrity and sovereignty; Mutual non-aggression; Mutual non-interference in domestic affairs; Equality and mutual benefit; Peaceful co-existence.

But today India’s prime minister has a better idea—something he calls “multi-alignment policy”. Behind what some commentators not without irony call a “grand vision” there are no more universal principles in the tradition of Kantian “eternal peace” but rather a very pragmatic idea of doing business with all. Without abandoning its independent course, India has moved to a contemporary, globalized practicality, according to which it will carefully balance closer cooperation with major players of today’s global geopolitics, like the US, Russia or China. It will do it in a way that advances country's economic and security interests, without being forced to choose one power over another.

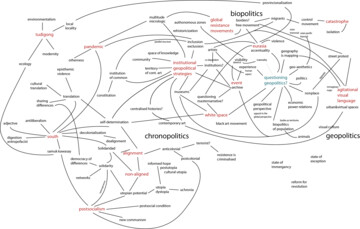

As long as a particular vision of international politics was based on no more than a pure negativity to alignment, there was no need to introduce the term into the vocabulary of geopolitics. But now, after the non-alignment has been turned into a multi-alignment claiming a similar strategic vision of international politics there is obviously sufficient reason to conceive of “alignment” as a new concept of the contemporary geopolitics.

The questions to be asked now must address the new division of the world into what once Carl Schmitt called large areas (Grossräume) and subsumed this historical condition under the notion of the “New Nomos on Earth”. If this condition has its geopolitics, alignment is its terminus technicus.